Is 2022 the Year California Gets Serious About Traffic Violence?

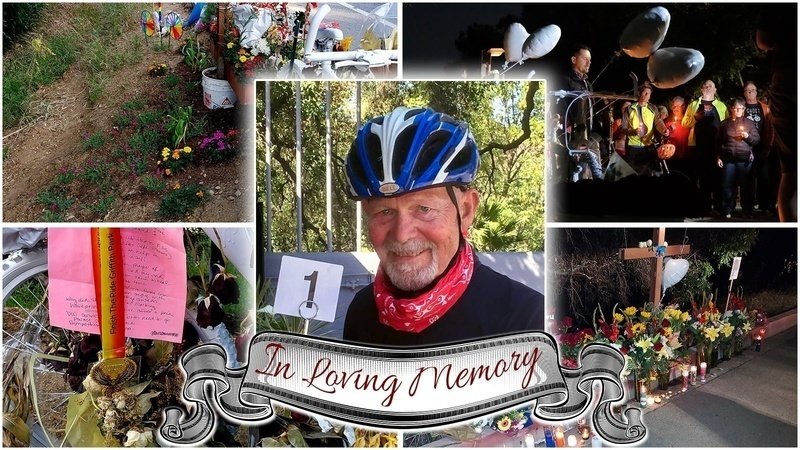

On April 16, 2022, a driver pulled around another car in Griffith Park and hit Andrew Jelmert at high speed, killing him. Jelmert was leading a training ride for the AIDS Lifecycle, a fundraising ride that the 77-year-old realtor had completed four times, so there was an unusual number of witnesses to his death. Unfortunately, he’s just one of many victims of traffic violence on California and U.S. streets. Unlike Jelmert, most of them are privately mourned by families with a hole where a loved one used to be.

CalBike has worked and continues to work to change the conditions that make California roads so deadly, especially for people biking and walking and particularly for our most vulnerable residents.

What makes a safe street?

The most recent statistics on traffic deaths are from 2020, when most of us stayed home to prevent the spread of COVID. That year, traffic violence killed 38,824 people in the U.S. California saw 3,847 traffic fatalities in 2020, an increase over 2019 despite less driving, and 3,246 people died on California streets in just the first nine months of 2021.

There are lots of reasons for the spike in traffic fatalities and injuries over the past few years, including:

- Drivers distracted by their devices and inattentive to the road

- New car and truck designs with taller and squarer front hoods that are more lethal, especially when a car driver hits a pedestrian

- Speeding on roads emptied by the pandemic

These causes center on driver responsibility, and drivers should be held accountable for their negligence. A new federal policy that will require automakers to consider the safety of people outside their vehicles, not just inside, is a step in the right direction. However, there is one thing that can significantly reduce injuries and deaths and make our streets safe for all users: infrastructure.

California has spent decades reshaping our communities to move more cars faster with little regard for the consequences. The people killed and injured are treated as collateral damage, an unavoidable downside to the civic good of giving people the ability to drive really fast in really big cars.

Changing perceptions of who has a right to community spaces

Traffic fatalities are only part of the violence wrought by car-first planning principles. Many more people survive collisions, but with injuries that can be life-changing. And the preference for speed and wide travel lanes ropes off large swaths of our civic space because people biking and walking can’t access it safely. That’s not counting the secondary injuries of car dependence: strokes, heart attacks, asthma, Alzheimer’s, and other diseases caused by breathing polluted air; the destruction of primarily Black and brown neighborhoods for freeway building; poor health outcomes due to lack of physical activity; and more.

Until recently, local and state governments accepted this status quo as our Faustian bargain for the miracle of motorized transport. In recent years, new laws plus changes in leadership and culture at California’s transportation agencies have begun to tip the balance ever so slightly toward building safer streets for everyone. The trend is continuing with this year’s raft of legislation. Could we be on the verge of the long-overdue transformation to truly bikeable and walkable communities across California?

Caltrans becomes part of the solution

After years of resisting almost any changes that shifted the agency from its singular focus on moving cars, Caltrans has been making promising changes. The agency began to take its own Complete Streets policy seriously after the 2019 appointment of Toks Omishakin as its director. Mr. Omishakin immediately ordered an overhaul of the state’s most significant funding program to identify bike and pedestrian safety improvements, moving $100 million into safety improvements. Omishakin was recently appointed as Secretary of CalSTA, where we expect he will bring his forward-thinking approach to California’s transportation authority.

The governor hasn’t named Omishaken’s successor at Caltrans yet, but we hope the next leader will continue the positive changes started during his tenure. And we witnessed the growing culture change at the recent California Bicycle Summit. At a session called State Leadership for a New Paradigm, Caltrans and CalSTA staffers both on the panel and in the audience voiced their determination to use Caltrans projects to create safer streets for people who bike and walk.

Bold policy change from a more bike-friendly legislature

In 2019, Senator Scott Wiener (San Francisco) introduced the country’s boldest complete streets mandate, requiring Caltrans to include safety improvements in repair and maintenance projects. Governor Newsom vetoed that bill, but it laid the foundation for the policy change at Caltrans that Omishakin implemented and oversaw.

Unfortunately, vetoing safe streets proposals has become a theme in Newsom’s administration. He vetoed a bill that would have brought bicycle highways and 15-minute neighborhoods to California and two other bills legalizing safe and practical use of the streets. The Freedom to Walk Act would have removed the prohibition against crossing midblock when no traffic is present. And the Bicycle Safety Stop would have allowed people on bikes to treat stop signs as yields, a reform already in place in eight states.

In 2021, the governor did sign AB 43, a critical bill that gives cities more latitude to reduce speed limits, creating safer streets. But we need much more to build neighborhoods and streets where people can safely walk and bike for everyday transportation. And that’s what CalBike is working toward in 2022, with many active transportation champions in the state legislature and a set of bills that could have a huge impact on California’s streets.

Opportunities for significant progress on active transportation in 2022

This year, CalBike is following and supporting a long list of bills that will positively impact our communities and provide alternatives to climate- and soul-killing modes of transportation. If these and several other bike-friendly bills become law, they will eventually change the shape of our communities, making them safer, greener, and more liveable.

CalBike’s two measures from 2021, legalizing pedestrian street crossings and the Bicycle Safety Stop, are back with revisions that promise to overcome the governor’s objections. And the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration recently published a safety fact sheet endorsing stop-as-yield laws as a way to increase safety and promote bicycling, adding weight to the arguments in favor of the safety stop.

Assemblymember Friedman has brought back her regional transportation planning bill, facilitating bicycle highways and reducing car parking requirements. In addition, she has introduced the OmniBike Bill, with numerous changes to traffic regulations that will make people on bikes safer. CalBike is cosponsoring an ambitious bill from Senator Anthony Portantino that will require cities to add bike infrastructure to their general plans—and then build it quickly.

Prioritizing active transportation in California’s budget

But these policy changes are just the beginning if we hope to accomplish the changes we need fast enough. Without funding, communities may have the best intentions to build better bikeways but not the means to carry out their plans, so money to build the infrastructure we need to make streets safer is crucial.

In the most recent round of funding for the Active Transportation Program, even with a budget boost, there was only enough money to greenlight a fraction of the worthy projects. CalBike is campaigning for $2 billion for bikes, which will add enough to the ATP to build many more excellent bike-friendly projects, plus provide funding to break ground on the revolutionary changes envisioned in this year’s legislation. As of this writing, the budget contains $1.1 billion for bikes, which is a huge victory. But we’re not stopping, especially now that the budget surplus has more than doubled to $68 billion.

Turning mourning into action

Andrew Jelmert left behind a husband, now widowed, and a community in mourning. Press accounts put the onus squarely on the driver, and the police took the incident seriously. The driver fled but was caught and charged with murder. With dozens of witnesses and 300 people on the training ride, this traffic death was hard to ignore or blame on the cyclist. Indeed, the incident has led to a petition to close Griffith Park to through traffic that has gotten about 1,600 signatures as of this writing.

But the response to this horrific incident is the exception, not the rule. Police in California still rule the bike rider at fault in about half of all bike-car collisions, data that the governor used to veto safety legislation in 2021.

Calling out traffic violence is the first step in taking it seriously and ending it. But programs like Vision Zero are meaningless if they aren’t backed by action, and blaming drivers or bike riders won’t solve the problem. Changing infrastructure will.

Hundreds of bike riders die or are injured on California streets each year, often without witnesses or fanfare, often in underserved communities where poor infrastructure makes the streets dangerous. The Ride of Silence (on May 18 this year) commemorates all the people on bikes lost to traffic violence around the world.

We need infrastructure that protects people on bikes from “mistakes” and “accidents.” California needs to spend money now to build the infrastructure we need to save lives. CalBike won’t stop advocating for that until there are no more Andrew Jelmerts killed by reckless driving, no more families and friends left bereft at the senseless toll of our dangerous roadways.

waltarrrrr/Flickr Creative CommonsCreative Commons

waltarrrrr/Flickr Creative CommonsCreative Commons