We’ve been getting a lot of questions about the e-bike purchase incentive project that CalBike helped pass and that the California Air Resources Board (CARB) is implementing. It’s an exciting program, and information hasn’t always been easy to come by. So we’ve compiled some of the most common questions from people who want to get a voucher, bike retailers who want to participate in the program, and others.

Pedal Ahead, the administrator CARB chose for this program, has published its own FAQs, which contain some additional information. Please note: Some of the information in the Pedal Ahead FAQs doesn’t agree with the information we have about the program. We have been told by CARB that some of the elements referenced in their FAQs are still under discussion. We will update our FAQs as we get additional information.

The official website for California’s E-Bike Incentive Project is live at ebikeincentives.org. You can get more information about how to apply for an incentive at that site (applications aren’t open yet), and bike retailers can sign up to participate.

Note: This post was originally written October 19, 2022, and last updated March 28, 2024.

TL;DR version:

- No, you can’t apply for an e-bike incentive yet. The program is expected to launch statewide in the spring of 2024, and applications will open then. We will announce the launch date as far in advance as we can.

- The pilot program is limited to Californians living at or below 300% of the federal poverty level.

- The voucher amount will likely be $1,000, with an extra $750 for a cargo or adaptive bike, and $250 additional for people below 225% FPL or living in a disadvantaged census tract.

- Incentives are limited to one per person. There is no limit per household.

- There are many local e-bike incentive programs. Visit our e-bike page for a full list.

What is California’s E-Bike Incentive Project?

The E-Bike Incentives Project is a program to provide vouchers to California residents to help them afford an e-bike. CalBike advocated for the budget allocation, which passed in 2021 and funds the pilot project. CARB has

The project will distribute $31 million in 2024, which will fund approximately 15,000 vouchers.

The California legislature hasn’t allocated ongoing funding for the program past the 2024 pilot, but CalBike will advocate for continued funding and CARB appears committed to including e-bikes in its clean vehicle incentive programs.

When can I apply for a California e-bike incentive?

As soon as the program launches, most likely in the second quarter of 2024.

You can’t apply in advance. However, if you sign up for CalBike’s e-bike mailing list below, we’ll let you know when the application window will open as soon as we get the date.

In the meantime, visit the program website to see if you’re eligible and find out what documentation you’ll need for proof of income.

Can I get an e-bike voucher from CalBike?

No.

CalBike is not administering the e-bike incentives program. Our role is one of advocacy. We advocated for the creation of this purchase incentive, and we will continue to push for an expanded budget to support the program. CalBike also shares critical information about the program via our e-bike newsletter, and we help our member’s voices be heard so that the program better serves the people who need it most. CalBike does not process or distribute incentives.

CARB will manage the incentive distribution process through its third-party administrator starting in 2023. We will share information about how to apply once it’s available, but CalBike won’t be involved in processing applications or awarding e-bike incentive vouchers.

Is California’s statewide program an expansion of the San Diego e-bike program?

No. Some press reports stated that California’s statewide purchase incentive was an expansion of a similar program in San Diego. This is incorrect.

CARB chose Pedal Ahead, an organization that runs an e-bike program in San Diego, to administer the statewide program. However, the CARB purchase incentives pilot will have rules and parameters determined by CARB in conjunction with input from advocates and the public. The statewide program is separate from and different from the San Diego program.

I already applied for an e-bike incentive. Am I in line? When will I get it?

At the April work group for the statewide program, several people stated that they had already applied for it. However, applications haven’t opened up yet. Even if you believe you applied for this incentive in the past, you will have to apply again once the application portal launches. Unfortunately, you aren’t in line for the statewide incentive (no one is yet).

Note: Signing up for CalBike’s list is a great way to stay up-to-date on the latest e-bike incentive news, but it is not an application for an incentive. That is a completely separate process in which you will need to prove income eligibility.

Can I get a rebate on an e-bike I already purchased?

No.

The Electric Bicycle Incentives Project is not a rebate program. You need to apply and get approved before you purchase a bike in order to use the incentive.

If you recently bought an e-bike, you might qualify for a rebate from a local program such as 511ContraCosta. Check the list on our e-bike page and ask your local utility about rebates. In addition, if the E-BIKE Act passes Congress, you might be eligible for a federal tax credit.

How do I apply for a voucher from California’s statewide e-bike incentives program?

The program administrator will set up an application process, and you will almost certainly be able to apply for the program online.

To apply, you’ll need documentation to prove that you meet the income qualifications. We’ll know more about the application process closer to the launch date.

What are the requirements to apply for an e-bike incentive?

You will have to prove income eligibility and California residency. We expect more information on specific documentation to be available soon.

Other requirements:

- Be at least 18 years old

- Purchase the bike within 90 days of incentive award

- Own the bike for one year

- Take a 30-minute bike safety education class online

Can more than one person in the same household apply for an e-bike voucher?

Yes.

Individuals can only get one voucher each, but there is no limit to how many people from the same household can apply, as long as each person qualifies.

How can I get assistance to buy an e-bike in California?

The E-Bike Incentives Project will be California’s first statewide e-bike voucher program. However, there are many regional and local programs where you might be able to get funding to help you buy an e-bike now.

SB 400, which CalBike helped pass in 2019, added an e-bike benefit to the Clean Cars for All program, which aims to take polluting cars off the road. If you have a qualifying car to turn in, incentives can be as high as $9,500, and you can use the funds to buy e-bikes and bike accessories for multiple family members. However, this program is administered by regional air quality management districts, and not all districts have added the e-bike benefit. We spoke to people who got this voucher in the Bay Area and Southern California to give you an idea of the process. Find out more details about the Bay Area program on this handy reference page.

In addition, there are numerous local programs through nonprofit organizations, utilities, and other entities. You can find many California programs on this list of global e-bike incentive programs.

Can I stack the California e-bike incentive with other e-bike incentives or rebates?

Yes.

If you qualify for a California voucher and an e-bike incentive from a local government, utility, transportation agency, or other entity, you may use both incentives toward the purchase of the same e-bike. This is called stacking. Some local programs are planning to work in tandem with the statewide incentives while others might not allow stacking; ask your local provider for more information.

How long does it take to get an e-bike incentive?

We don’t know how long the application process will take through the statewide program, but it will involve income verification and then finding an eligible bike vendor, so plan on at least a few weeks (and possibly longer) from when you apply.

For the Clean Cars program, the people we interviewed waited quite a few months to get through paperwork and approvals. For local programs, inquire directly about the timing.

Bottom line: If you need an e-bike ASAP, you might not want to wait to get a voucher.

Who will qualify for the California e-bike incentive program?

Eligibility for the pilot program will be limited to people whose income is less than 300% of the federal poverty level. That means the income caps (based on 2024 FPL guidelines) would be:

- Individual: $45,180

- Family of 2: $61,320

- Family of 3: $77,460

- Family of 4: $93,600

- Family of 5: $109,740

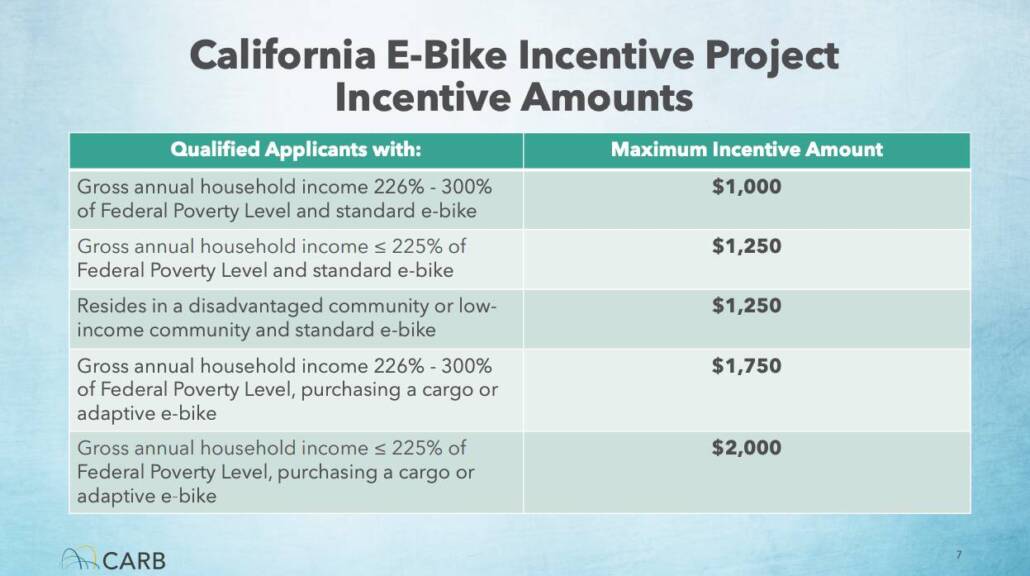

How much will the California e-bike incentives be?

The base incentive will be $1,000. The program will offer an additional $750 for people buying a cargo or adaptive bike and another $250 for people living below 225% of the federal poverty level or living in a disadvantaged community. The maximum incentive is $2,000.

What kinds of bikes qualify for incentives?

You can use the incentive to buy any type of e-bike, including a folding bike, cargo bike, or adaptive bike. All three classes of e-bikes will be eligible for the program. However, you will need to purchase from a list of approved e-bike models.

E-bikes are grouped into three classes:

- Class 1: pedal assist only, 20 mph speed limited — will qualify for the program

- Class 2: pedal assist or throttle, 20 mph speed limited — will qualify for the program

- Class 3: pedal assist only, 28 mph speed limited, helmets required, must be 16 or older to operate — likely to qualify for the program

Note: Only bicycles that include pedals, fall into one of these three classifications, and are offered by an approved retailer qualify for the incentive program. Other forms of electric mobility, such as scooters and mopeds, are not included.

What qualifies as an adaptive bike?

CARB wants to keep the definition of adaptive bike as inclusive as possible. The category will most likely include tricycles and bikes modified for people with disabilities.

Can I use an e-bike incentive to buy a conversion kit?

A conversion kit allows you to add aftermarket electric power to a standard bike frame. Conversion kits are not eligible for incentives.

Can I buy bike accessories to go with my bike?

Yes. If you are awarded an incentive through the California program and your bike purchase, including sales tax, is less than the amount of your voucher, you can buy gear for your ride with the remaining balance. At the moment, the only allowed purchases are helmets and other unspecified “safety gear.” CARB has stated that it specifically won’t fund the purchase of reflective clothing or bike cargo racks, but we hope that policy shifts, based on public comment. We also hope that locks will be included in the allowed purchase items.

Why can’t I get an incentive to buy a non-electric bike?

Excellent question. The current program covers only electric bike purchases, not standard or classic bikes. Electric bikes tend to be significantly more expensive than classic bikes, so a purchase incentive may be the only way for many people to afford one. In addition, many people who don’t feel comfortable riding a standard bike because of age, health issues, the need to carry passengers or cargo, etc., may replace car trips with bike trips on an electric bike.

However, the classic bicycle is incredibly energy-efficient and elegant transportation, and some places do offer incentives to help residents buy non-motorized bicycles. For example, the French government is offering 400 Euros to citizens who trade their cars for a bike or e-bike. CalBike would love to see a program like this in California and we will continue to explore ways to encourage more people to choose the joy of riding a bike.

Where can I buy an e-bike with a CARB incentive?

The program administrator will provide a list of qualifying bike retailers. You can buy from a bike shop or order an e-bike online.

How do I purchase a bike with an incentive?

The statewide incentive will be a point-of-sale benefit. Once you pick out a bike from a qualifying retailer, the incentive amount will be applied when you make the purchase. You don’t have to put out that money up front and get reimbursed.

I’m an e-bike retailer. How can I participate in the program?

Retailers can apply online through the program website. Qualifying retailers must have some kind of physical presence in California (a shop, office, or manufacturing facility), even if you sell your bikes exclusively online. You may need to supply parts to local retailers so participants can have access to repairs and service.

Will there be more e-bike incentives next year, or is this a one-time program?

E-bike incentives are very popular, so we hope this program will continue, but there are no guarantees. Sign up for CalBike’s list if you’re willing to boost our advocacy by sending emails to your elected leaders in support of future funding for e-bike incentives.

How do I get more information about the e-bike incentive program?

Have we mentioned that CalBike has an e-bike incentives interest list? Use the form below to add your name, and we’ll send periodic updates as we get more information, including letting you know when you can apply.

You can also sign up for CARB’s e-bike email list to get information directly from CARB or sign up for the E-Bike Incentives Project email list.