Senate to Hear SAFER Streets Package

MEDIA ADVISORY for April 23, 2024

Contact: Jared Sanchez, CalBike, (714) 262-0921, Jared@CalBike.org

SAFER Streets Bills to Be Heard at Senate Transportation Committee on Tuesday, April 23, 2024

SACRAMENTO – The Senate Transportation Committee will convene on April 23, 2024, at 1:30 p.m. to discuss the SAFER California Streets package of bills. The hearing will take place at 1021 O Street, Room 1200, Sacramento State Capitol, and will be televised.

The Speeding and Fatality Emergency Reduction on California Streets (SAFER California Streets) Package, comprising Senate Bills 960 and 961 authored by Senator Scott Wiener, aims to enhance safety and accessibility on California roads for all users.

The SAFER California Streets package will have the combined effect of creating safe passage for people biking, walking, and taking transit through infrastructure improvements and simple vehicle safety measures.

As traffic fatalities surge across the United States, particularly in California, amid a spike in reckless driving since the pandemic’s onset, the urgency for such measures is undeniable. According to a recent report by TRIP, a national transportation research group, California has witnessed a 22% increase in traffic fatalities from 2019 to 2022, compared to the national average of 19%. Shockingly, in 2022 alone, 4,400 Californians lost their lives in car crashes.

“Other nations are making progress to protect road users, while in the U.S., the problem grows steadily worse,” said Jared Sanchez, policy director for CalBike. “CalBike is proud to sponsor the SAFER California Streets bills because the continuing killing and maiming of vulnerable road users on California’s streets must end.”

The SAFER Streets Bills

SB 960: Complete Streets Bill

SB 960, The Complete Streets Bill of 2024, mandates Caltrans to incorporate safe infrastructure for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users when repaving state routes serving as local streets. The bill includes provisions for transit needs, facilitating the establishment of more bus-only state highway lanes and transit enhancements on local streets. The Complete Streets Bill requires Caltrans to establish objective goals and prioritize the implementation of comfortable, convenient, and connected facilities for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users.

SB 961: Safe Vehicles Save Lives Bill

SB 961 protects vulnerable road users by focusing on vehicle safety enhancements. This bill mandates the installation of truck side guards to protect cyclists and pedestrians from being pulled beneath the rear wheels of trucks during accidents. Side guards also prevent cars from running under trucks during crashes, significantly reducing fatalities.

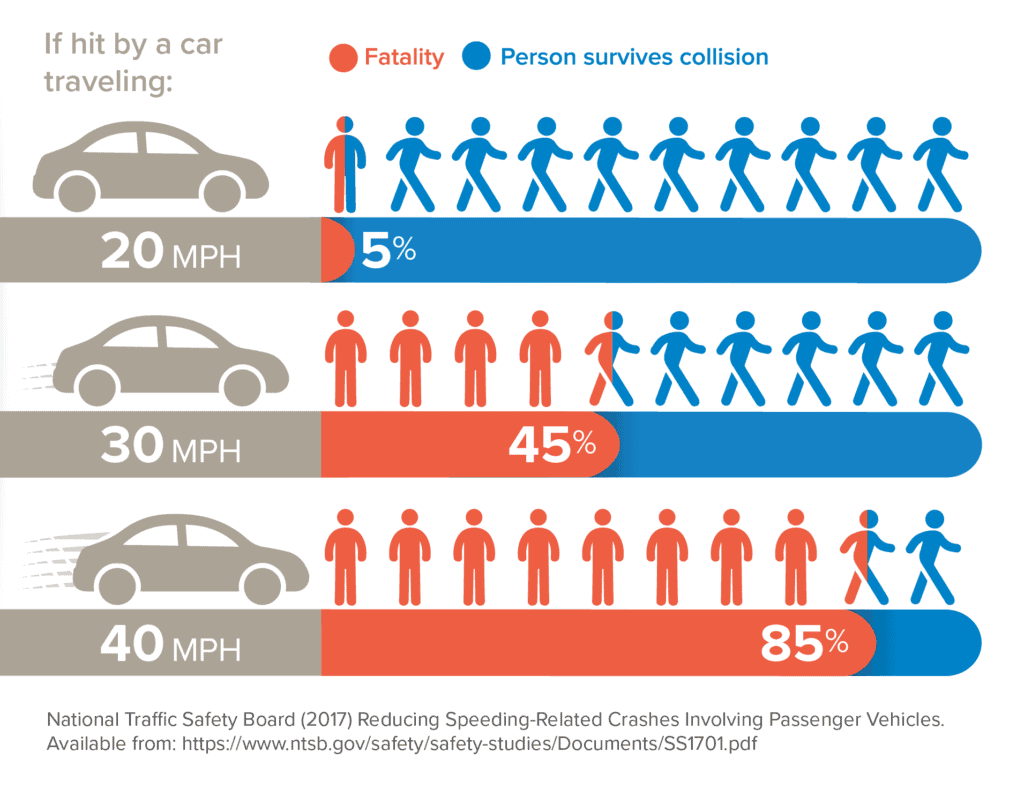

Additionally, SB 961 requires speed governors or intelligent speed assistance (ISA) technology in all passenger cars sold in California from the 2032 model year onwards. ISA technology will warn a driver when the vehicle exceeds the speed limit through visual, sound, or haptic alerts and is expected to reduce fatalities among pedestrians and cyclists, aligning with the state’s Vision Zero goals. The EU has implemented a similar law, with ISA required on new cars starting this July.

These bills represent a comprehensive approach to tackling the pressing issue of road safety in California, addressing both infrastructure and vehicle safety concerns. The outcome of the Senate Transportation Committee hearing on April 23, 2024, holds the potential to catalyze transformative changes that will save lives and make California’s streets safer for all.

CalBike Backgrounders

Truck Side Guards: A Low-Cost Hack That Would Save Lives and Money

Slowing Cars to Save Lives

Hundreds Attend CalBike Complete Streets Campaign Launch with Senator Wiener

Injuries and Deaths Caused by Trucks without Side Guards

Bicyclist Hit by Big Rig on San Vicente at Santa Monica This Morning

Bicyclist dies in Long Beach hit-and-run crash with big rig, police say

Pedestrian Killed By Big-Rig Last Week Identified As Kentucky Woman

Male Pedestrian Dead is after Being Hit by a Big Rig on Highway 99 at Esplanade

Injuries and Deaths Caused by Speeding

Woman charged with manslaughter in Carlsbad crash that killed 3-bike rider

One of my dearest friends, Julia Elkin, was struck and killed by a car last month

Speeding driver hits, kills bicyclist in Hayward

Video Two Anaheim teenagers hospitalized after speeding car hits them on the sidewalk