New State Law Leads to $90M for San Diego Bike Projects

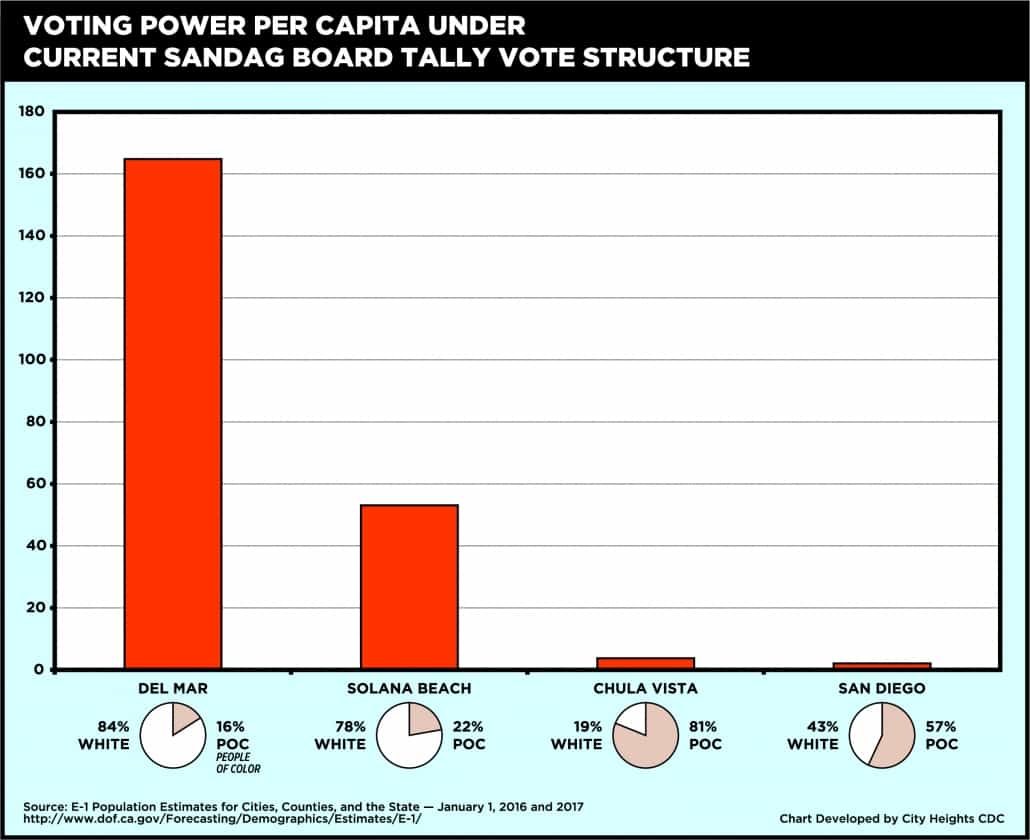

Advocates for San Diego bike projects used to find themselves stymied by the conflicting values of a regional agency that was controlled by votes representing suburban residents. Those residents, more likely to be affluent and white, had more voting power per capita. Residents of the more populous cities that had less voting power were likely to be less affluent communities of color. In 2017, advocates refused to accept that unequal power structure and mobilized to change the way the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) voted on projects. With the support of Assembly Member Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher and CalBike’s help, they changed state law to make SANDAG more democratic, giving more weight to votes representing more people.

The new voting process was used most recently to pass a $90 million bond that will provide funding to finish several bike projects in the San Diego region. The unweighted vote on the bond was a tie. With a second vote under the new weighted vote process, the bond measure passed the SANDAG board, 62-38.

“Advocates for improvements in active transportation often have an uphill battle. One of the problems is an entrenched power structure that amplifies the voice of richer, whiter communities while shutting out communities of color and poorer residents,” said Jared Sanchez, CalBike Senior Policy Advocate. That’s why passing AB 805 was a priority for CalBike.

The new weighted voting structure at SANDAG, which went into effect in 2018, has been used several times. This is the story of how a law passed in Sacramento can be an important tool for advocates fighting for transportation equity in their community in San Diego.

Before AB 805: Suburban Communities Blocked San Diego Bike Projects

SANDAG is a regional decision-making agency for the San Diego area. Its board includes representatives from 18 cities and the county of San Diego. The problem with the board’s structure has been that San Diego (population 1.42 million) had the same voting power as smaller cities such as Del Mar (population 4,363 ).

This unequal distribution of power allowed small cities, which were more suburban, to dictate planning decisions. What this often meant is that SANDAG’s urban planning choices were car-centric. San Diego was not able to pursue transit, biking, and walking projects that would benefit its denser population and residents who are less well-off than many in surrounding communities.

Randy Torres-Van Vleck, Senior Program Manager, Transportation & Planning at the City Heights Community Development Corporation (City Heights CDC), realized that residents couldn’t win the projects they needed under the SANDAG structure. “Because of the way the board voting power was structured at SANDAG, it made it very difficult for environmental justice communities and the largest cities in the region to exert self-determination,” he said. “Suburban cities could vote to widen a freeway in our city. It took away residents’ ability to protect their own health.”

So Torres-Van Vleck’s organization decided to do something about it.

City Heights CDC Fights for Transportation Equity

The city of East San Diego became part of San Diego 100 years ago. It is now the City Heights neighborhood. “Because it was its own city, it has distinctive neighborhoods within it,” said Vianney Ruvalcaba, Transportation Planning Coordinator for the City Heights CDC. The neighborhood has become a safe haven for immigrants and refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, Somalia, and Latin America. Residents speak 35 languages and 200 dialects. The diversity makes City Heights a beautiful place, according to Ruvalcaba. She added, “Unfortunately, it’s also been a victim of environmental racist policies that prioritize suburban development and freeways.”

City Heights CDC was formed to fight environmental racism. “One of the reasons why we exist is because Caltrans planned a freeway through the middle of the area in the 1970s,” Ruvalcaba said. The CDC fought hard to underground a section of the freeway to keep it from cutting the community in two, as freeway developments did in neighborhoods of color in many other California cities. The organization hired planners and organizers and put environmental lawyers on their board. “We were forced to become experts around these issues,” she said. “As a result, we became leaders in transportation justice.”

While the neighborhood didn’t get everything it wanted, it won significant mitigations, including a new bike path. There is even a documentary film about their victory.

This put the City Heights CDC in a good position to identify the environmental justice issues in the SANDAG voting structure. Torres-Van Vleck watched the board vote to widen freeways in communities that were already suffering from the highest levels of pollution. He called this “doubling down on the wrongs of the past.”

So City Heights CDC began to float the idea of a bill that would change the power structure at SANDAG.

All About AB 805

The bill that would pass in 2017 as AB 805 changed the weighted voting structure of the SANDAG board. Members can call for a second, weighted vote after a board vote, if three representatives on the board agree to it. The weighted system created under AB 805 allocates votes to the cities on the board based on population. In the new process, the votes of more populous San Diego carry more weight than votes from smaller cities. The results of the weighted vote supersede the original vote.

SANDAG voting power per capita before AB 805.

It wasn’t a slam dunk that the legislature would pass this measure. Torres-Van Vleck noted that factors such as a scandal at SANDAG in 2017 helped convince stakeholders that change was needed. Local Assembly Member Lorena Gonzalez introduced the bill and championed it in the legislature.

While City Heights CDC and partners lobbied hard for AB 805 from San Diego, CalBike worked to get the bill signed into law in Sacramento.

CalBike Partnered with Local Advocates to Help Pass Vital Legislation in Sacramento

CalBike’s policy advocates partnered with City Heights CDC organizers to push AB 805 in Sacramento. “Regional power structures often serve to reinforce control by those that already have power and marginalize low-income communities of color,” said Sanchez. “AB 805 was important because it gave us the chance to change the balance of power and give voice to under-served communities.”

City Heights CDC lobbied city members of SANDAG for support. “Every city in San Diego County weighed in on AB 805,” Torres-Van Vleck said. “We were going around the region talking about democracy and power.”

For City Heights CDC, it was also important to have good partners in Sacramento. Sanchez and CalBike Policy Director Linda Khamoushian kept their local partners in the loop. They served as the lead advocates for the bill at the capital. “CalBike has been a great watchdog for us in Sacramento,” Torres-Van Vleck said. “Their support for AB 805 was important.”

AB 805 Has a Big Impact on San Diego Bike Projects

AB 805 became law and went into effect in 2018. Torres-Van Vleck feels that the impact of this power shift has been huge. “It was the most transformative policy that I’ve ever seen implemented in my 10 years of doing this work,” he said. “It changed San Diego for the better.”

Since 2018, the new weighted vote structure has been used four or five times. “It has been used for votes that allow for transportation justice and better represent the voices of the community,” said Torres-Van Vleck. “That’s good for bikes, it’s good for transit, it’s good for housing.”

The success of AB 805 has even won over some people who were opposed to it at first. Before Stephan Vance retired in 2018, he worked at SANDAG for 36 years, most of that in the agency’s active transportation program (he was also a long-time board member of CalBike). He didn’t like what he saw as a heavy-handed approach in the bill. “The culture at SANDAG was that everything operated on consensus,” he said. The agency tried to make all parties happy and avoid split votes. “The downside of that is that stuff gets watered down because you make a lot of compromises.”

“Now that I’m on the outside and advocating for some of the things these small cities are challenging, I like the weighted vote,” Vance said. “Otherwise, they would be preventing very reasonable things from happening.” He sees the new voting structure as a crucial tool for achieving big changes in California’s transportation systems. Not only is that necessary to meet greenhouse gas emissions targets set by the state, but it is also the only way to unclog roadways.

“We have to change to accommodate growth and to save our climate. We can’t let backward-looking people dictate transportation policy anymore,” Vance said. “Democracy is served [by AB 805]. No longer can representatives of a minority of the region’s population dictate policy.”

A change in voting rules for a planning board might seem far removed from the on-the-ground fights of local advocates. The story of AB 805 illustrates that state legislation can have a big impact on local streets.