Reduce the Role of Police in Traffic Enforcement for the Safety of Everyone

Update: Following on the August 24 police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, WI, on August 31, a Los Angeles sheriff’s deputy stopped a Black man for riding his bike the wrong way on a quiet residential street. Moments later, the officer shot Dijon Kizzee dead.

This has to stop. Will you sign our call for action?

It’s time to end armed police traffic enforcement.

I support increased safety for everyone who uses our public streets, and alternatives to our current reliance on armed police officers to enforce traffic rules.

CalBike supports the efforts of community leaders across California to reduce or eliminate the role of police in traffic enforcement. Inspired and educated by these leaders, and focused on changes to state policy, we have drafted six recommendations to advance that cause while improving transportation safety. We will continue to work with local leaders to prioritize and take action on the most important recommendations.

What the Defund the Police Movement Means for Bicycling

Originally published July 27, 2020: City leaders across California and the nation are hearing loud calls to “defund the police” after popular protests have highlighted the failure of reform efforts to reverse a history of police violence against Black people. While some use the phrase as a call for the abolition of police, most traffic safety advocates in California are coming to agreement on a more moderate appeal. This includes a call to reduce police budgets and redirect resources to social workers, homeless advocates, healthcare providers, and others who could better address community needs. CalBike supports this shift in funding and focus because we believe it will do more to keep us safe, while bringing us closer to the goal of eliminating violent anti-Blackness from our streets and civic spaces.

CalBike believes that a shift in traffic safety focus and funding away from policing and towards community resources is a more effective way to create safe streets.

There is growing momentum to shift funding from policing to community resources, including a movement to take traffic enforcement out of the hands of armed officers.

- “By reinvesting in services such as mental health, violence prevention, education, and safe street systems, our communities can work toward a new type of public safety that does not involve armed police,” wrote Bike East Bay in a recent article “Cut Police Budgets, Invest in Community and Transportation.

- “Safer streets, designed in partnership with the community, reduce the need for police enforcement of speeding.” Bike East Bay, Police-Free Systems Are Possible.

- “It is clear to us that legacies of discrimination and racism pervade our transportation system; people of color suffer disproportionately from traffic violence and a lack of access to dignified mobility options. Now, as we face an unprecedented public health crisis, Black and Brown Angelenos are being disproportionately affected by the economic and health disparities laid bare by COVID-19.” The Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition

- “Though it has not been SVBC’s primary strategy, SVBC will not be encouraging enforcement as a solution and will examine alternatives to traditional types of traffic enforcement until there is a means to achieve equitable enforcement.” Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition

- On July 15, the City of Berkeley, approved a restructuring of its police department. The measure will, among other reforms, create a BerkDOT for traffic enforcement “with a racial justice lens,” removing this function from its police department.

- Berkeley is the first California city to take this step but probably not the last. LA City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson told NBC’s Los Angeles affiliate, “I’ve had a gun pointed at me five times in my life. Four times were police officers. Once was a person trying to rob me.” Harris-Dawson has proposed placing the responsibility for traffic stops with the LA Department of Transportation, not the police.

Ongoing racist police enforcement of traffic laws makes these proposals a priority. Traffic stops are the place where most people are likely to come into contact with the police. When you factor in the data on racial disparities in police use of force, racial disparities in traffic policing are even more problematic. A 2018 analysis by Vox found that police were more likely to use force against unarmed Black people and much more likely to kill Black people who aren’t resisting arrest. Thus, some of the most well known instances of violence against Black Americans began during traffic stops, including Rodney King in 1991 and, more recently, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, and many others.

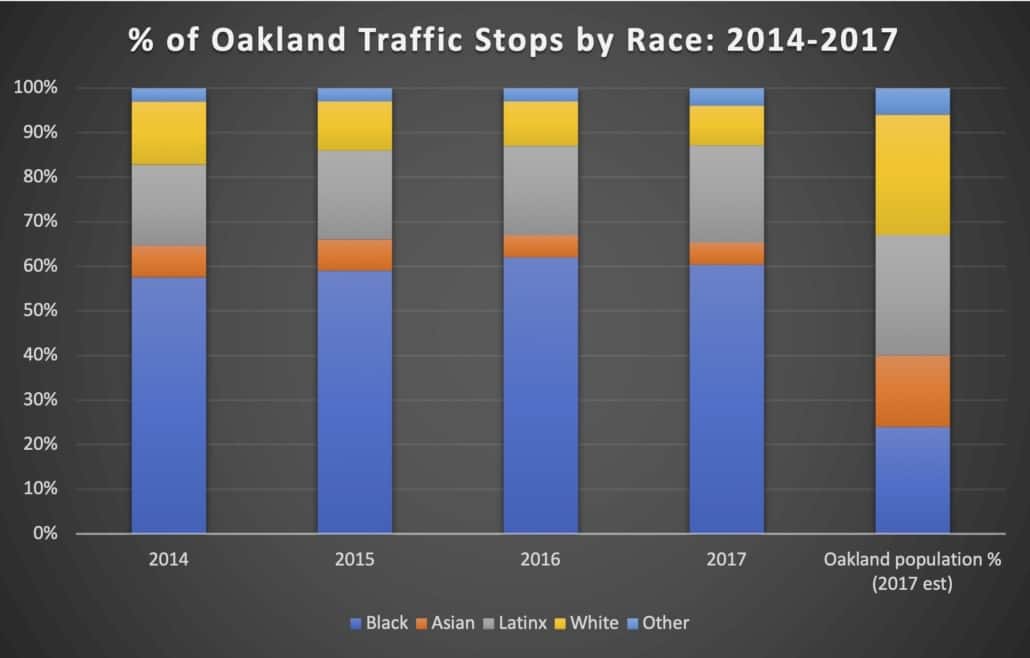

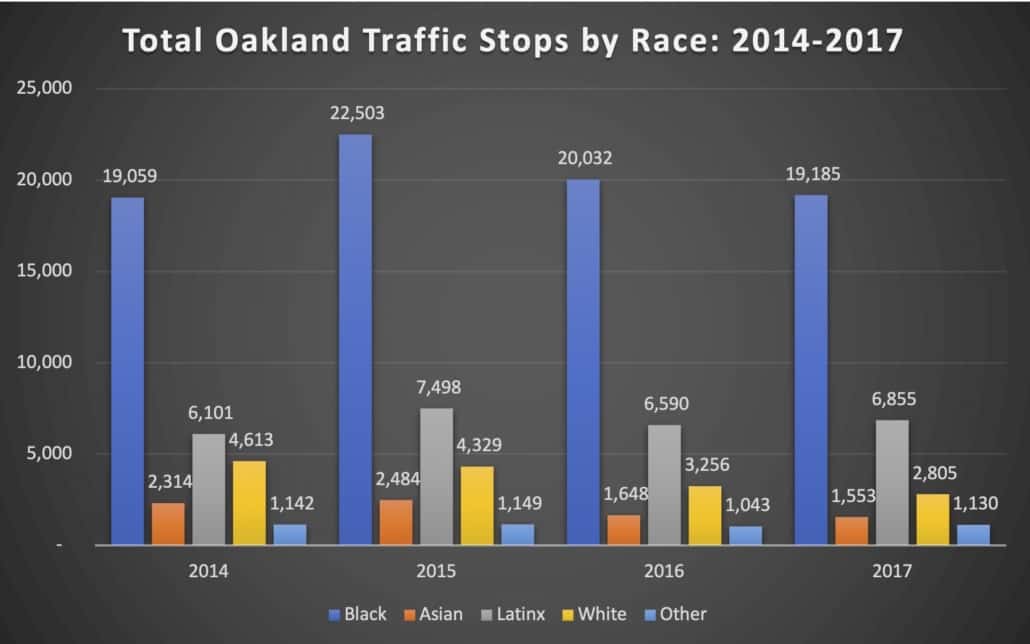

Racial profiling extends to police enforcement against people on bikes, too. Bike East Bay has crunched the numbers on traffic stops in Oakland and they are stark:

Source: Data compiled by Bike East Bay

Source: Data compiled by Bike East Bay

Source: Data compiled by Bike East Bay

Source: Data compiled by Bike East Bay

No one should be harassed for biking or walking while Black. No one should be threatened with police violence for using shared public space. Enforcement of traffic laws by armed police is not working to create safe streets. In fact, it is downright dangerous to Black, indigenous, and people of color.

CalBike proposals to create safe streets for all Californians

Inspired by the movements across California and around the country, including an excellent report by Transportation Alternatives in New York, CalBike endorses proposals to get police out of traffic enforcement.

We can’t achieve our goals as long as racism makes our streets unsafe for Black and brown people to bike, walk, or simply exist. Bicycling cannot “enable people to live a healthy and joyful life” if the streets are dangerous because of the color of your skin. Fighting against racism is inextricably part of advocating for equitable, prosperous, inclusive communities. To be true to our mission, CalBike must fight against anti-Black violence with the same zeal that we fight against policies that disadvantage biking and walking.

In this report, CalBike makes six recommendations for state policy changes that will shift traffic enforcement in an anti-racist direction.

- Redirect funding from the CHP budget to street redesign

- Redirect funding from the CHP to automated enforcement

- Divert Office of Traffic Safety (OTS) funding from police departments to community efforts

- Decriminalize biking and walking

- Make public transportation, including bike and scooter share, free

- Implement income-adjusted traffic fines

We believe these policies will reduce the threat to Black and brown people from unreformed police forces. They will allow officials to redirect substantial funding away from bloated and overly militarized police departments and into programs that will be more effective in creating safe streets. These measures will move California closer to meeting other important, official goals, like reducing vehicle miles traveled to save the climate and improve public health. They represent a big step toward our vision of an equitable, prosperous, and inclusive California, where everyone has the chance to be healthy and joyful, by, for example, riding a bike.

Recommendation 1: Redirect funding from the California Highway Patrol budget to street redesign

California’s transportation budget allocates $2.5 billion to the California Highway Patrol (CHP). That’s three times more than public transit assistance and 11 times more than the severely underfunded Active Transportation Program (ATP).

At the current funding level of $220 million per year, the ATP can pay to build the infrastructure necessary to meet California’s goal of tripling bicycling … in 36 years. Tripling bicycling will reduce traffic crashes, improve safety, and reduce injuries and violence on the streets better than police. In fact, if California were to abolish the CHP and direct its entire budget to active transportation projects, we could build a statewide bike network to triple bicycling in a little over four years.

Building protected bike lanes is a traffic safety measure. A 2019 study found that protected bike lanes reduced traffic fatalities for all modes of travel by 44% and serious injuries by 50%.

Our streets can be redesigned to be “self-enforcing. While infrastructure changes have a high up-front cost, they are much less expensive over time than policing. Safer infrastructure is operational 24/7 and doesn’t require staffing. Better yet, protected bike lanes and intersections have no racial bias – they are equally safe for everyone.

It’s important, also, to prioritize these investments in the state’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods, where malign neglect has created racialized disparities in economic security, health outcomes, and traffic safety. Repaving, repairs, and safety upgrades in these neighborhoods and in collaboration with residents will be a good start toward correcting some of that historical disinvestment.

Recommendation 2: Redirect funding from the CHP to implement automated enforcement

Studies show that automated speed cameras can reduce speeds by up to 15% and serious car crashes by up to 44%. That’s a lot better than we’re doing now. While car crash fatalities have mostly trended down since a high of over 54,000 in 1972, they have trended upward again in recent years. California’s Zero Fatalities Task Force (of which CalBike is a member), reported that New York City had reduced speed in school zones by 60% by installing speed cameras. While the task force report recommended speed cameras as a supplement to policing, not a replacement, CalBike believes that there is no place for armed officers in traffic enforcement.

While speed and red light cameras are a good substitute for biased policing, we must make sure that the placement of cameras is unbiased. Cameras need to be spaced throughout communities, not concentrated in disadvantaged neighborhoods. We can’t use ticket revenue extracted from poor communities to plug holes in municipal budgets (more on this later).

One of the most effective places to put traffic cameras is on public buses. These cameras can detect and ticket double parking, stopping in bus zones, and other violations that slow down transit and make it a less appealing option than driving a personal car. Currently, we are aware of only two transit systems, both in the Bay Area, that mount cameras on buses. As Streetsblog reported when San Francisco first installed theirs, state law prohibits these cameras from issuing moving violations. The technology has continuously improved, so that state law should change. Buses would be very effective at providing roving violation detection.

Recommendation 3: Divert Office of Traffic Safety funding from police departments

The state Office of Traffic Safety (OTS) distributes more than $90 million in federal safety grants to organizations and agencies across California. Most OTS priorities center around enforcement, so most of that money goes to police departments to pay overtime to officers for dubious or counter-productive traffic enforcement efforts. For example, when the Berkeley police got a Vision Zero grant from OTS, it used half the money to send police out to ticket bike riders for running stop signs. (In Berkeley, the backlash was so fierce that the city told its police force to stop enforcing bicycle stop sign violations.)

Bicycles and pedestrians cause few if any injuries and even fewer deaths on California streets. Traffic enforcement should target the vehicles that cause the most harm: cars and trucks. In addition, people who walk and bike have to contend with a hostile built environment that often doesn’t serve them. What the police see as violations are often merely bike riders making their best choices about how to get around on poorly designed streets.

Recommendation 4: Decriminalize common behaviors

The only way to make our streets safe for everyone is to stop ticketing people for biking and walking. These violations contribute little or nothing to traffic violence. Police can use these tickets to harass and penalize people for walking or biking while Black. Our society loses much more than it gains.

- Running stop signs and red lights on bikes.

The “Idaho stop” refers to a 1982 Idaho law that allows people riding bikes to treat stop signs as yields and red lights as stop signs. While other states have followed suit in recent years, the California vehicle code does not allow it. Some local jurisdictions have endorsed one or both of these measures and directed their police forces not to issue tickets. CalBike supports a change to the California vehicle code to make the Idaho stop legal statewide. - Crossing on foot midblock or against the light.

The concept of “jaywalking” was created by car manufacturers to deflect the blame for pedestrian fatalities away from drivers and onto walkers. Research has shown that pedestrians cross where there aren’t crosswalks when the built infrastructure doesn’t meet the needs of people who walk. Jaywalking is an offense that may be selectively enforced and shouldn’t actually be a crime at all. - Riding a bike as a child without a helmet.

“Children” as old as 17 are required to wear a helmet when they ride a bike in California. Many don’t, which gives police a reason to harass them. Studies are inconclusive on whether the child helmet law reduces child head injuries. This law should be replaced with funding for a statewide program to hand out helmets to people of all ages who need them. Ditto for bike lights, which are required for riding at night.

Recommendation 5: Make public transportation, including bike and scooter share, free

Tickets for fare evasion are most likely to be given to the people who have the least means to pay. Transit police often target Black riders for extra scrutiny. CalBike has long supported proposals to make public transit a free service for everyone. The money saved on transit policing will help make free transit more affordable.

Three bills from the state legislature this year would have mandated free transit for youth, students, and seniors – all of which we supported. In previous years Asm. Chris Holden pursued this goal, but his legislation was vetoed by Governor Brown. Brown justified his veto because the bill didn’t identify a funding source. At least some of those funds can be provided by reducing police budgets. We need buses for people, not tanks for police.

Shared bikes and scooters should be considered part of public transit systems. Bikes and scooters should be ubiquitous, especially in predominantly Black neighborhoods, and reach way beyond the urban core into the suburbs. Rides should be free. Short of that, fees should be at least as low as or lower than public transit, with integrated fares and free transfers.

Recommendation 6: Implement income-adjusted fines

In Finland, traffic fines are assessed by income and can be higher than $100,000. In California, too, fines for traffic violations across the board should be variable based on income.

If traffic fines are truly meant as a deterrent, this is essential. A $200 red light ticket could take food off the table of a minimum wage worker, but amount to spare change for a wealthy person. Traffic fines reinforce cycles of poverty and discrimination, often leading to harsher penalties and late fees for poor people who can’t afford to pay. No one should go hungry or go to jail because of a traffic violation.

Next Steps

We need as many voices as possible asking for these reforms. Please sign our petition if you support these recommendations.

CalBike didn’t create these policy recommendations on our own. These ideas come from community leaders, grassroots activists, and transportation policy professionals from around the world. We are inspired by their leadership, especially Black and brown urbanists like Tamika Butler, who have been speaking out about racism in planning and policing for years.

CalBike is committed to continuing to listen, to better understand the racial impacts of transportation policy so we can better align our values and actions with anti-racism. We will change our recommendations and priorities as necessary, and continue to fight for anti-racist transportation policies that support healthy, bikeable, safe streets for BIPOC Californians.